A Brief History of Ancient Iranian Art

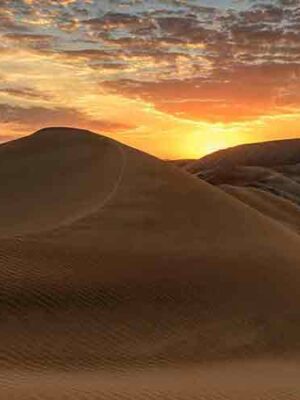

To many historians, ancient Persian art is still a mystery to unravel. It developed and evolved at a crossroads of ancient civilizations and cultures. The land we call Iran today was on a highway connecting Africa to the Indian subcontinent and beyond from very early times. Modern man also crossed Iran to get to the plains of Central Asia. Those who settled in what is present-day Iran left their artistic mark in the caves of the west of Iran and the formidable Zagros range settlements in the shape of early tools and petroglyphs.

Some of these ancient peoples formed early civilizations in ancient Iran that were parallel to those of Mesopotamia in power and culture. These early civilizations soon produced art that was compatible with that of Mesopotamia and Egypt. The art produced was on par with art forms anywhere in the ancient world. With an abundance of sites existing across northeastern, northern, and northwestern Iran, Bronze Age Elam dominated the scene in southwestern and southern parts of Iran.

The Elamites

The Elamites were the indigenous people of the Iranian plateau who had surpassed other rivals in some art forms. They excelled in metallurgy and pottery as well as embroidery and glazing. In Art history, a life-size bronze statue of the Elamite queen Naparisha, as well as a tremendous number of items were recovered from excavations carried out in Elamite cities such as Susa. Some of these include pendants offered to the Elamite God Inshushinak, found in the rubble beneath the deity’s temple dating from the 12th century BC. Yet, the already exquisite art forms of the Elamites were to be advanced upon with the arrival of a migrant race of people infusing their art form and interacting with neighboring regional powers.

Enter the Indo-Europeans

The Indo-Europeans began to arrive on the Iranian plateau in multiple influxes from the 3rd millennium BC with the 2nd millennium B.C influx being the most major one. Tappeh Sialk, a much earlier settlement, can perhaps serve as their most acclaimed early settlements of the central plateau with artifacts as elaborate as the bridge-spouted vessels of the early 1st millennium BC. These artifacts resemble birds and the spouts were also drawn out dramatically to resemble bird beaks.

The remains of metal-smelting furnaces at the site and pottery workshops testify to the artistic taste of these long-forgotten people. The necropolis or Sialk VI was where a large number of great undamaged artifacts were retrieved. Sialk comprises two mounds; the northern and the southern. Pottery shards still litter both mound surfaces. The level of craftsmanship in both mounds is significant and the existence of painted pottery dating back to much earlier periods is abundant. A continuation of artistic talent persisted throughout those distant periods. Ancient Persian art traditions had not yet flourish, but with the arrival of the Indo-Europeans, ancient Persian Art was only around the corner.

Luristan Art

Luristan is famous for its late 2nd-millennium early 1st-millennium art which includes a great variety of funerary items including axe-heads, mace-heads, and women’s hairpins. Horse bits with amazing cheek-pieces and horse harness ornaments were also common. The archeologists obtained these items mainly from necropolises that flanked springs where skeletons of horses lied. This indicates that there was a belief in the afterlife. Standards, as well as effigies of deities, have also been found in the same graves. Mesopotamian deities such as Sin, the moon God of the Mesopotamians, and Shamash, their Sun God are often depicted on such artifacts.

Luristan Bronze

The Caspian Region

In the southwest of the Caspian Sea, sits the 1st millennium B.C site of Marlik, which once enjoyed an advanced civilization producing artful pieces of golden, silver, and bronze artifacts that included various vessels as well as weapons of war, and ceramics which demonstrated high levels of ancient technology. Polished ceramics, Bulls on wheels, and hunched-back bulls indicate a rich pastoral mode of life. Job division had long existed and the quality of the art attests to that. The high levels of precipitation in the region ensured a prosperous agrarian existence which allowed artistic expenditure.

Merging Artistic traditions

In the 8th century B.C, a fusion of a number of different cultures such as Urartian, Median, and Assyrian art cultures combined. They produced art forms sometimes attributed to Mannaeans, who lived south of Lake Urumia, in northwestern Iran and were sometimes allied with the Assyrians. Amongst some of the better-known sites identified with the Mannaeans are Ziwiyeh near the town of Saqqiz where in 1947, ivory, gold, and bronze objects came to light. They probably fell to an invasion by the Scythians, whose early artwork resembles Mannaean artifacts. Scythians, a people of the steppes of central and northwestern Asia, were themselves artistic in nature. They soon incorporated Urartian art, as well as other cultures they encountered.

Median Period

The Medes first appear on the historic scene as the Amadai in Annals of the Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III in 836 B.C together with the Persians (Parsuas).

The Median king, Cyaxares, sacked the Assyrian capital, Nineveh in 612 B.C .The Medes have left us architectural feats artwork such as their magnificent capital, the legendary Ecbatana mentioned by Herodotus.

Achaemenian Period

The Achaemenid period is perhaps the first great era of ancient Persian art of the historic period. Firstly, the Medes, the overlords of western Asia after their decisive victory over the mighty Assyrians inherited the great artistic heritage of the various peoples of their empire. Subsequently, the Persians inherited the artistic wealth and tradition of these earlier civilizations.

The Achaemenids incorporated an international and eclectic approach in their art and architecture, culminating in the magnificent palaces of Pasargadae and Persepolis where ancient Persian art has borrowed from Mesopotamian art and architecture. Although some Egyptian ideas were explored, ancient Persian art and architecture is for the most part Persian & Elamite in origin.

Immortal Guards

Pasargadae

The site of the first capital of the Persian Empire, Pasargadae, sits on a high plain 110 km north of Shiraz where Cyrus the Great lies in his tomb. It has a ziggurat-shaped architecture and sits amidst the plain. Cyrus defeated his grandfather and overlord, Astyages, King of Media in this plain. The art employed in Pasargadae, now termed ancient Persian art, is eclectic. For instance, there were winged bulls which formed the main Gateway palace entrances of which only small fragments survive.

Four-winged guardian spirits, also known as winged genies, flank the side entrances to the gatehouse. The single surviving figure is wearing a long Elamite outfit with the head surmounted by a sophisticated Egyptian-style headdress. “I, Cyrus, king, the Achaemenian” trilingual inscription that once existed, had survived above the surviving up to the 19th century. ‘An Assyrian style “Fishman and Bullman” occupies the Reception palace gateway entrance on one side. On the opposite side, one can see the lower part of a man’s figure, followed by the lower part of the figure of a bird beast.

Winged Genius

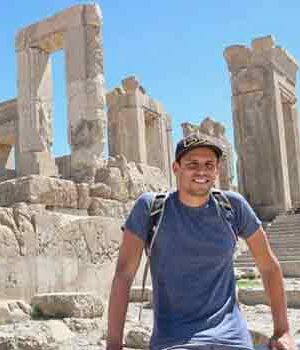

Persepolis

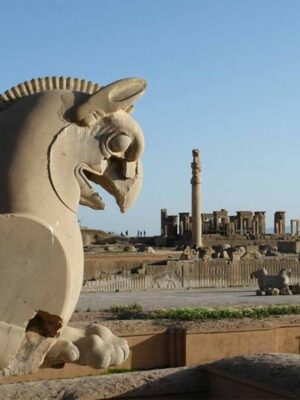

Persepolis sits on a huge platform above the Marvdasht plain and looks west toward the plain from which side travelers used to approach the site in ancient times. Above the unique staircase, the “Gate of All Nations” has welcomed travelers from distant times. The Two guardian bulls facing west were simple bulls, while the ones facing east, were lumasi. Although not ancient purely Persian art, these winged, human-headed guardians are in naturalistic form as opposed to Assyrian examples.

Gate of All Nations

Eastern Staircase of the Apadana

The magnificent Eastern Staircase of the Apadana palace carries carvings of 28 tribute-bearing delegations from across the Persian Empire. Ancient Persian art here includes scenes of delegations moving into the palace for an audience with the king. The delegations range from the Ethiopian on one end, to The Medes on the other. Each delegation carries tributes special to their country of origin. For example, Indians with their vessels of spices, and Ionian Greeks with their tribute of wool. Tachara, the private palace of Darius the Great, carries cuneiform inscriptions by him. However, the larger Palace of Xerxes, the “Hadish” has a slightly different style to the private palace Darius.

The Queen’s Quarters

Professor Herzfeld reconstructed the Queen’s private palace that now houses a small charming museum where he employed Ancient Persian art very similar to the rest of Persepolis. Through glass-covered openings in the floor, one can see sections of the original floor. The capitals here are wooden with bulls, similar to other bulls in Persepolis with mythological significance.

The Throne Hall of Xerxes

The Achaemenids made “Throne Hall of Xerxes” to accommodate a large number of people. Each doorway’s decoration carries a different theme. The main entrance approaching from the Gate of All Nations”, houses 50 Immortal Guards on each side. The Immortal Guards formed the elite unit of the Persian Army from the time of Darius the Great. They comprised Persian and Medes who stand shoulder to shoulder to each other.

The ancient Persian art here is also mythological. For instance, the northern exit to the Eastern Staircase of the Apadana is where Xerxes is slaying a lion. This lion is representative of the demon of drought, Aposha. By this, The Persian king wishes to state his authority over all forces of nature, good and evil.

The Treasury

They stored all the tributes brought by the delegations in the treasury. Alexander of Macedon carried hundreds of camel and mule loads of it in 331 B.C. Important tablets came to light here from underneath the silt and rubble in the twentieth century. These tablets, known as Persepolis Treasury Tablets, have shed great light on the workers. Their gender, the amount of payments, the form the payments took, and who authorized the payments are on record.

The tablets written between 506-497 B.C, were the size of the palm of the hand and they provide interesting information. For instance, they show that paid labor built the site and not a slave force and that some of the heads of the workshops were female. Although the workers were from all over the empire, ancient Persian art was dominant throughout the site.

Persian Art of the Achaemenids

The architectural Persian art carries a unique signature that is overwhelmingly Persian even if all the elements were not. The architects made use of the best of everything available to them, which is a trait found only in true empire builders. Persepolis was a place of peace, not violence, where delegates and noblemen stood graciously in harmony. This was the true spirit of the Persians, which one also finds on the Cylinder Seal of Cyrus the Great. Where the ancient world disregarded tolerance of different ideas, the Persians embraced this virtue in their art and architecture.

A Brief History of Ancient Iranian Art

To many historians, ancient Persian art is still a mystery to unravel. It developed and evolved at a crossroads of ancient civilizations and cultures. The land we call Iran today was on a highway connecting Africa to the Indian subcontinent and beyond from very early times. Modern man also crossed Iran to get to the plains of Central Asia. Those who settled in what is present-day Iran left their artistic mark in the caves of the west of Iran and the formidable Zagros range settlements in the shape of early tools and petroglyphs.

Some of these ancient peoples formed early civilizations in ancient Iran that were parallel to those of Mesopotamia in power and culture. These early civilizations soon produced art that was compatible with that of Mesopotamia and Egypt. The art produced was on par with art forms anywhere in the ancient world. With an abundance of sites existing across northeastern, northern, and northwestern Iran, Bronze Age Elam dominated the scene in southwestern and southern parts of Iran.

The Elamites

The Elamites were the indigenous people of the Iranian plateau who had surpassed other rivals in some art forms. They excelled in metallurgy and pottery as well as embroidery and glazing. In Art history, a life-size bronze statue of the Elamite queen Naparisha, as well as a tremendous number of items were recovered from excavations carried out in Elamite cities such as Susa. Some of these include pendants offered to the Elamite God Inshushinak, found in the rubble beneath the deity’s temple dating from the 12th century BC. Yet, the already exquisite art forms of the Elamites were to be advanced upon with the arrival of a migrant race of people infusing their art form and interacting with neighboring regional powers.

Enter the Indo-Europeans

The Indo-Europeans began to arrive on the Iranian plateau in multiple influxes from the 3rd millennium BC with the 2nd millennium B.C influx being the most major one. Tappeh Sialk, a much earlier settlement, can perhaps serve as their most acclaimed early settlements of the central plateau with artifacts as elaborate as the bridge-spouted vessels of the early 1st millennium BC. These artifacts resemble birds and the spouts were also drawn out dramatically to resemble bird beaks.

The remains of metal-smelting furnaces at the site and pottery workshops testify to the artistic taste of these long-forgotten people. The necropolis or Sialk VI was where a large number of great undamaged artifacts were retrieved. Sialk comprises two mounds; the northern and the southern. Pottery shards still litter both mound surfaces. The level of craftsmanship in both mounds is significant and the existence of painted pottery dating back to much earlier periods is abundant. A continuation of artistic talent persisted throughout those distant periods. Ancient Persian art traditions had not yet flourish, but with the arrival of the Indo-Europeans, ancient Persian Art was only around the corner.

Luristan Art

Luristan is famous for its late 2nd-millennium early 1st-millennium art which includes a great variety of funerary items including axe-heads, mace-heads, and women’s hairpins. Horse bits with amazing cheek-pieces and horse harness ornaments were also common. The archeologists obtained these items mainly from necropolises that flanked springs where skeletons of horses lied. This indicates that there was a belief in the afterlife. Standards, as well as effigies of deities, have also been found in the same graves. Mesopotamian deities such as Sin, the moon God of the Mesopotamians, and Shamash, their Sun God are often depicted on such artifacts.

Luristan Bronze

The Caspian Region

In the southwest of the Caspian Sea, sits the 1st millennium B.C site of Marlik, which once enjoyed an advanced civilization producing artful pieces of golden, silver, and bronze artifacts that included various vessels as well as weapons of war, and ceramics which demonstrated high levels of ancient technology. Polished ceramics, Bulls on wheels, and hunched-back bulls indicate a rich pastoral mode of life. Job division had long existed and the quality of the art attests to that. The high levels of precipitation in the region ensured a prosperous agrarian existence which allowed artistic expenditure.

Merging Artistic traditions

In the 8th century B.C, a fusion of a number of different cultures such as Urartian, Median, and Assyrian art cultures combined. They produced art forms sometimes attributed to Mannaeans, who lived south of Lake Urumia, in northwestern Iran and were sometimes allied with the Assyrians. Amongst some of the better-known sites identified with the Mannaeans are Ziwiyeh near the town of Saqqiz where in 1947, ivory, gold, and bronze objects came to light. They probably fell to an invasion by the Scythians, whose early artwork resembles Mannaean artifacts. Scythians, a people of the steppes of central and northwestern Asia, were themselves artistic in nature. They soon incorporated Urartian art, as well as other cultures they encountered.

Median Period

The Medes first appear on the historic scene as the Amadai in Annals of the Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III in 836 B.C together with the Persians (Parsuas).

The Median king, Cyaxares, sacked the Assyrian capital, Nineveh in 612 B.C .The Medes have left us architectural feats artwork such as their magnificent capital, the legendary Ecbatana mentioned by Herodotus.

Achaemenian Period

The Achaemenid period is perhaps the first great era of ancient Persian art of the historic period. Firstly, the Medes, the overlords of western Asia after their decisive victory over the mighty Assyrians inherited the great artistic heritage of the various peoples of their empire. Subsequently, the Persians inherited the artistic wealth and tradition of these earlier civilizations.

The Achaemenids incorporated an international and eclectic approach in their art and architecture, culminating in the magnificent palaces of Pasargadae and Persepolis where ancient Persian art has borrowed from Mesopotamian art and architecture. Although some Egyptian ideas were explored, ancient Persian art and architecture is for the most part Persian & Elamite in origin.

Immortal Guards

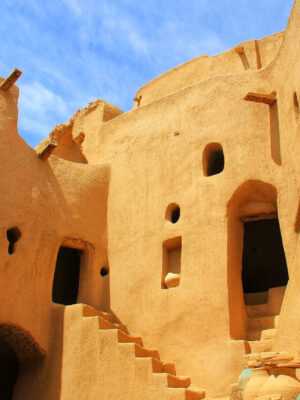

Pasargadae

The site of the first capital of the Persian Empire, Pasargadae, sits on a high plain 110 km north of Shiraz where Cyrus the Great lies in his tomb. It has a ziggurat-shaped architecture and sits amidst the plain. Cyrus defeated his grandfather and overlord, Astyages, King of Media in this plain. The art employed in Pasargadae, now termed ancient Persian art, is eclectic. For instance, there were winged bulls which formed the main Gateway palace entrances of which only small fragments survive.

Four-winged guardian spirits, also known as winged genies, flank the side entrances to the gatehouse. The single surviving figure is wearing a long Elamite outfit with the head surmounted by a sophisticated Egyptian-style headdress. “I, Cyrus, king, the Achaemenian” trilingual inscription that once existed, had survived above the surviving up to the 19th century. ‘An Assyrian style “Fishman and Bullman” occupies the Reception palace gateway entrance on one side. On the opposite side, one can see the lower part of a man’s figure, followed by the lower part of the figure of a bird beast.

Winged Genius

Persepolis

Persepolis sits on a huge platform above the Marvdasht plain and looks west toward the plain from which side travelers used to approach the site in ancient times. Above the unique staircase, the “Gate of All Nations” has welcomed travelers from distant times. The Two guardian bulls facing west were simple bulls, while the ones facing east, were lumasi. Although not ancient purely Persian art, these winged, human-headed guardians are in naturalistic form as opposed to Assyrian examples.

Gate of All Nations

Eastern Staircase of the Apadana

The magnificent Eastern Staircase of the Apadana palace carries carvings of 28 tribute-bearing delegations from across the Persian Empire. Ancient Persian art here includes scenes of delegations moving into the palace for an audience with the king. The delegations range from the Ethiopian on one end, to The Medes on the other. Each delegation carries tributes special to their country of origin. For example, Indians with their vessels of spices, and Ionian Greeks with their tribute of wool. Tachara, the private palace of Darius the Great, carries cuneiform inscriptions by him. However, the larger Palace of Xerxes, the “Hadish” has a slightly different style to the private palace Darius.

The Queen’s Quarters

Professor Herzfeld reconstructed the Queen’s private palace that now houses a small charming museum where he employed Ancient Persian art very similar to the rest of Persepolis. Through glass-covered openings in the floor, one can see sections of the original floor. The capitals here are wooden with bulls, similar to other bulls in Persepolis with mythological significance.

The Throne Hall of Xerxes

The Achaemenids made “Throne Hall of Xerxes” to accommodate a large number of people. Each doorway’s decoration carries a different theme. The main entrance approaching from the Gate of All Nations”, houses 50 Immortal Guards on each side. The Immortal Guards formed the elite unit of the Persian Army from the time of Darius the Great. They comprised Persian and Medes who stand shoulder to shoulder to each other.

The ancient Persian art here is also mythological. For instance, the northern exit to the Eastern Staircase of the Apadana is where Xerxes is slaying a lion. This lion is representative of the demon of drought, Aposha. By this, The Persian king wishes to state his authority over all forces of nature, good and evil.

The Treasury

They stored all the tributes brought by the delegations in the treasury. Alexander of Macedon carried hundreds of camel and mule loads of it in 331 B.C. Important tablets came to light here from underneath the silt and rubble in the twentieth century. These tablets, known as Persepolis Treasury Tablets, have shed great light on the workers. Their gender, the amount of payments, the form the payments took, and who authorized the payments are on record.

The tablets written between 506-497 B.C, were the size of the palm of the hand and they provide interesting information. For instance, they show that paid labor built the site and not a slave force and that some of the heads of the workshops were female. Although the workers were from all over the empire, ancient Persian art was dominant throughout the site.

Persian Art of the Achaemenids

The architectural Persian art carries a unique signature that is overwhelmingly Persian even if all the elements were not. The architects made use of the best of everything available to them, which is a trait found only in true empire builders. Persepolis was a place of peace, not violence, where delegates and noblemen stood graciously in harmony. This was the true spirit of the Persians, which one also finds on the Cylinder Seal of Cyrus the Great. Where the ancient world disregarded tolerance of different ideas, the Persians embraced this virtue in their art and architecture.